The Loewenstein Family: A Story of Survival

Nazi violence and persecution had escalated since Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. Kristallnacht (November 9-10, 1938) made it clear that Jews in Germany were doomed. The Loewensteins fled their home, taking shelter at the apartment of Max's brother Georg, who had already been seized by the Nazis. Two days later, Henry went back to check if the Nazis had been in the apartment. Then, with his mother, loaded a box with the family silver and tried to leave it with Aryan friends until things calmed down. “We pushed the box around on my bike for several hours, but no one wanted to open their door for us, being more concerned with their own safety,” recalled Henry.

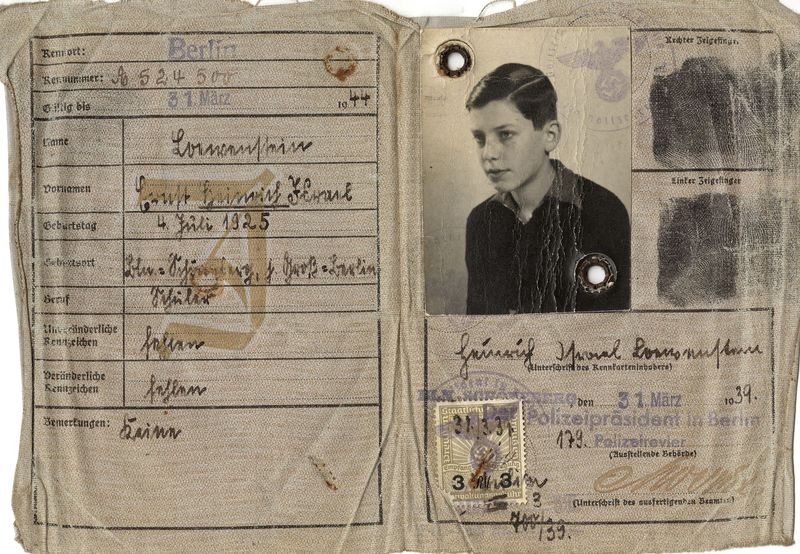

Following Kristallnacht, Jews were required to carry identity cards issued by the Gestapo. Dr. Max Loewenstein and Henry were issued their cards at Gestapo headquarters on March 31, 1939 in Berlin. For Henry it was a significant moment as he watched his father, who had always been a commanding presence, endure the insults screamed at him by the Gestapo’s bureaucrats. Henry later recalled that this was the moment he truly realized the hopelessness of the family’s situation.

Jews, desperate to leave Germany, Austria, and occupied Czechoslovakia, were only allowed to take a very small amount of money out of the country. Other countries, still struggling to feed their own people at the end of the Great Depression, could not afford to take these penniless refugees. Henry’s cousin, Ingrid Lind, was lucky enough to have Danish citizenship and escaped to Denmark. When the Germans occupied Denmark in 1940, she escaped alone to Sweden and Finland. At age nineteen, she crossed Russia into the Middle East on foot, where she joined the British Army.

Max had previously applied for visas to the United States and investigated other emigration options for the family, but nothing appeared to be possible for at least another three years. Jews were not likely to be able to survive that long under Nazi rule. The family barely survived in Berlin until the end of World War II.

Henry was able to escape to England through a British refugee program known as the Kindertransport.